Giyur refusal reasons: How to avoid them

Giyur, or converting to Judaism, is also a deep spiritual transformation and commitment to Jewish law and community. And for many, it is also the way to claim Israeli citizenship according to Israel’s Law of Return. But driving this challenging process is hard and it is vital to know all sides of it and where it can go wrong. Many candidates are suddenly being rejected at the last moment by rabbinical courts (Beit din), preventing them from coming to the Israel. In this in-depth guide we explore the fundamental reasons for being denied acceptance and actionable steps to improve your chances to gain acceptance. We explore the procedural aspects, pitfalls and halachos that will enable you to embark on this life-altering odyssey with knowledge and reassurance.

an Israeli citizenship specialist

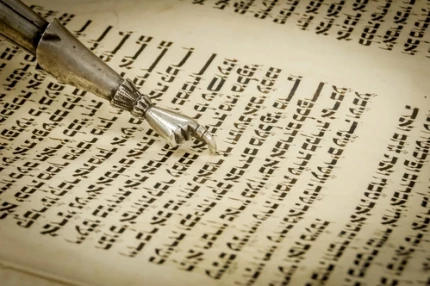

Understanding the Giyur process

The giyur process is overseen by an Orthodox Beit Din (a rabbinical court), acceptance by which is only required for citizenship in Israel. Whereas Reform or Conservative conversions — often not accepted by Israeli authorities — an Orthodox conversion would guarantee compliance with the standards set by the Chief Rabbinate. It is usually a 1–2 year process that takes place in a series of stages: an introductory period with a sponsoring rabbi, a period of integration into the Jewish community, an educational period culminating in a series of formal interviews and rituals in front of the Beit Din, an additional intensive education in Torah, Halakha, and Jewish ritual, and accepting the commandments at a final meeting with the Beit Din.

Both sexes undergo tevilah (immersion in a mikveh). The Beit Din assesses the sincerity of the candidate, their degree of observance (Shabbat, kashrut etc.), and their entrance into Jewish community life. The bottom line: Conversions begun outside Israel are more vulnerable to challenge: Nonresident applicants need the blessing of the Exceptions Committee, a government entity that judges their sincerity. After conversion, candidates apply for citizenship and present their giyur certificate to Israel’s Ministry of Interior. This invokes an independent verification mechanism that cross references documentation, and sometimes interviews candidates, to corroborate their claims to the Beit Din. Obstacles or denials at this stage often are a result of the candidate’s answers not collating with their giyur testimony.

Common reasons for Giyur refusal

In many cases, denial by the Beit Din (or Ministry of Interior) is grounded in known obstacles. Knowing these causes enables candidates to take steps to minimize weaknesses:

Another important acceptance criterion that usually is neglected in the realm of double knee replacement is psychological preparedness. Kosher candidates who buckle under the weight of lifestyle shifts — or who can’t find the words to describe how they will negotiate obstacles such as social isolation or kosher compliance — come off as uncertain. The Beit Din reads this as a concern regarding post-giyur lapsing in observance.

How to avoid Giyur refusal

This chapter will walk you through the most common causes of giyur refusal, and more importantly, offer clear, practical steps to avoid them. From choosing the right rabbinical court to maintaining a consistent Jewish lifestyle and understanding bureaucratic expectations, careful preparation is key. Whether you are considering Orthodox, Conservative, or Reform conversion, understanding the system — and working with experienced advisors — will significantly increase your chances of a successful and recognized giyur. Proactive mitigation of refusal reasons significantly elevates success odds. Implement these evidence-based strategies throughout your giyur journey.

Choose Your Rabbi and Community Meticulously

Align exclusively with an Orthodox community under the Israeli Chief Rabbinate’s authority. Verify their conversion track record via the Jewish Agency or Rabbinic Court websites. A respected sponsoring rabbi lends credibility; their detailed endorsement letter to the Beit Din can counter doubts about sincerity or knowledge depth. Avoid transient affiliations — sustained involvement (18–24 months) demonstrates authentic integration.

Document Rigorously and Transparently

Compile a giyur portfolio including:

- Certified translations of vital documents (birth/marriage certificates).

- Police clearance certificates from all countries of residence.

- A chronological personal essay detailing your spiritual evolution.

- Logs of Shabbat/holiday observance, kosher practice, and community events attended.

Anticipate documentation issues by disclosing complexities (e.g., prior religious affiliations, gaps in records) early to your rabbi. They can strategize halakhic solutions or preemptive explanations to the Beit Din.

Master Practical Halakha and Interview Nuances

Beyond textual study, prioritize applied Judaism. Practice prayers, kosher cooking, and Shabbat rituals until they feel natural. Prepare for the Beit Din interview by rehearsing answers to probing questions: “How will you handle not driving on Shabbat?” “Describe your last Passover Seder.” Demonstrate emotional resonance — not just rote answers. If applicable, coordinate mock interviews with your rabbi.

Leverage Legal Pathways for Non-Residents

Non-Israeli candidates must obtain Exceptions Committee approval before beginning giyur. Submit a petition emphasizing spiritual motives — not Israeli residency desires. Include proof of future Jewish community engagement in your home country (e.g., letters from local synagogues). If rejected, consult an immigration lawyer specializing in giyur issues; appeals based on procedural errors or new evidence sometimes succeed.

Post-Conversion Vigilance

After receiving your giyur certificate, maintain meticulous observance until citizenship confirmation. Ministry of Interior officials may observe candidates or conduct surprise interviews. Any divergence from commitments made to the Beit Din — such as working on Shabbat shortly after conversion — fuels refusal reasons related to insincerity. Consider delaying Aliyah until your Jewish lifestyle feels unshakeable. Navigating giyur demands spiritual authenticity and strategic preparation. By internalizing Judaism’s rhythms, securing credible mentorship, and preempting bureaucratic pitfalls, candidates transform refusal risks into a pathway of profound belonging.

Legal aspects and challenges

For instance, candidates with prior ties to anti-Israel groups face heightened scrutiny, and gaps in personal records (e.g., unresolved divorces under Jewish law) can trigger rejections. The Ministry of Interior conducts post-conversion audits, comparing interview testimonies with lifestyle observations—a discrepancy like working on Shabbat may validate suspicions of insincerity. Additionally, non-residents who begin giyur without pre-approval from the Exceptions Committee face near-certain rejection, as this violates procedural criteria designed to filter immigration-motivated applications.

Halakhic controversies further complicate acceptance. While traditional din holds that conversion is irrevocable once rituals are completed (Yevamot 47b), some Orthodox courts now retroactively annul conversions if post-facto non-observance suggests insincere intent during the process. This approach, championed by figures like Rabbi Avraham Sherman, was contested in high-profile cases like Rabbi Druckman’s overturned annulments, highlighting jurisdictional fractures.

Preparing for Beit Din and conversion

Thriving before the beit din hinges on immersive preparation that transcends theoretical knowledge. Candidates should allocate 12–24 months to embed Jewish practice into daily life, focusing on halakha (e.g., kashrut, Shabbat) rather than academic study alone. A strategic, five-phase approach minimizes refusal risks:

- Step 1: Community Integration– Join an Orthodox synagogue under Rabbinate authority. Attend services weekly, participate in holiday events, and secure a mentorship rabbi. Document involvement through photos, event logs, and leader testimonials to demonstrate authentic belonging.

- Step 2: Halakha Internalization– Transform rituals into habitual practice. Work with your rabbi to implement kosher kitchen protocols, Shabbat electronics restrictions, and daily prayer routines. Maintain journals detailing challenges and adaptations.

- Step 3: Documentation Audit– Compile certified birth/marriage certificates, divorce decrees (if applicable), and police clearances. Address discrepancies early (e.g., missing apostilles) with legal assistance to avoid bureaucratic pitfalls.

- Step 4: Ritual Preparation– Men schedule hatafat dam brit with approved mohelim. Both genders rehearse mikveh immersion protocols. Coordinate ritual dates around Jewish holidays when batei din prioritize sincerity evaluations.

- Step 5: Interview Simulation – Conduct biweekly mock sessions with your rabbi tackling questions like “How does Shabbat observance align with your career?”Record responses to refine authenticity and body language.

Interview readiness demands emotional honesty alongside factual knowledge. Judges probe for lived Judaism – describe tactile experiences like kneading challah or lighting Hanukkah candles rather than quoting texts. If anxiety arises, request written Q&A formats; some panels permit this accommodation. Post-ritual, sustain observant practices for 6+ months before Aliyah applications. Ministry officials may verify consistency through neighbor testimonials or unannounced home checks, where deviations risk rejection.

FAQ

Halakha traditionally deems giyur irrevocable upon ritual completion (Yevamot 47b). However, some Orthodox courts have controversially invalidated conversions retroactively if post-facto non-observance suggests deceit during the process. Precedents like Rabbi Sherman’s 2008 ruling against Rabbi Druckman’s converts were later overturned, reflecting deep ideological rifts.

Yes, per the Law of Return and Supreme Court rulings. However, the Chief Rabbinate rejects them for marriage or burial. Non-Orthodox candidates face extra scrutiny: expect extended background checks and demands for proof of sustained community ties.

Judges evaluate behavioral consistency, not declarations. They cross-reference testimonies about Shabbat observance or kosher practice with rabbinic reports and community feedback. Suspicion arises if candidates avoid integrating with Jewish social networks or resist discussing spiritual growth.

Yes, but symbolic hatafat dam brit (drawing a blood drop) remains mandatory. The procedure must be overseen by a beit din-authorized mohel (ritual circumciser) and documented with medical certificates.

Physical limitations don’t preclude conversion, but cognitive barriers may. Deaf candidates historically faced refusal due to communication barriers, but today, interpreters and written Q&A are often permitted. Mental competency to understand mitzvot is essential.

If the child was under 12 during the parent’s giyur and raised Jewish, they’re typically recognized as Jewish without additional rituals. Teens aged 13+ undergo their own abbreviated process, emphasizing personal commitment.

While halakha considers you Jewish regardless, such actions may trigger state investigations. The Ministry of Interior can revoke citizenship if fraud is proven, though this requires exhaustive evidence like public renunciations of Judaism.

an Israeli citizenship specialist